Deplatforming an Infrastructure: a critical cartography of Huawei’s 5G technology

- Introduction

The House Intelligence committee of the U.S. has released reports since 2012 accusing two Chinese telecommunication giants as a vehicle for Chinese espionage and has warned American companies from buying their equipment (Greene and Tibken). One of the two companies is Huawei, a transnational Chinese company that is the second largest phone manufacturer and the biggest telecom networking equipment supplier in the world (Keane). These accusations were later addressed and put into action in May of 2018 when President Donald Trump issued an executive order that placed Huawei and several Chinese affiliates on the “Entity List” (Stewart). This is a trade blacklist that prevented U.S. companies from buying and selling components and software to companies like Huawei without the government’s approval as it is a potential threat to national security. This discourse quickly escalated to become part of the trade war between the U.S. and China as major tech giants such as Google, Intel, Qualcomm needed to quickly adapt to the change of national policy and cut their business ties with Huawei.

Major infrastructures at risk due to the situation is the telecommunication industry, which is currently transitioning from 4G to 5G technology as Huawei holds the largest global share in deploying the most efficient wireless networking technology (Stewart). The U.S. is also constantly pressuring its allies to block Huawei and find other alternatives for 5G networking such as Sweden’s Ericsson or Finland’s Nokia to prevent long-term surveillance and manipulation form the Chinese government. This in turn could ultimately slow down the implementation of global 5G networks as Huawei offers the most efficient equipment for the cheapest price (Kania and Sheppard). Despite the warnings, many nations still proceed with Huawei as their potential choice for 5G networking as their current infrastructure is already built using the company’s equipment (Porter). One example is the UK; although they consider Huawei as a national cyber security threat, they still allowed Huawei to capture 35 percent of the market share (Porter). Meanwhile, nations in proximity to the U.S. like Japan have completely excluded Huawei’s equipment from its infrastructure (Kyodo). These examples underline the overall narrative of how nations are either pledging or not pledging its allegiance to the Trump administration, which could potentially be mapped to trace global relations and influence from the U.S.

This research makes use of critical cartography practices as described in Jeremy Crampton’s book on the subject in order to analyze what impact this deplatforming effort has on both Huawei itself and other relevant stakeholders. This is done through the research question “How have Huawei and its business practices been affected by different actors as a result of deplatforming efforts?” This research bases itself on several theoretical pillars in order to answer this question. Using Crampton’s framework as a start, this research employs the critical mapping approach by situating this deplatforming effort by the U.S. government in specific geographic spaces, and examining closely the decision-making process that seeks to uncover the relationship between power and knowledge.

The entities mapped by this research include several different stakeholders that are interrelated in various ways. The main relations are the relation between Huawei and the U.S. government that makes an effort to delatform Huawei based mostly on accusations of espionage; the relation between Huawei and other tech companies, both collaborators and competitors, who are all affected in some way by these developments; and the relations between the U.S. government and other allied governments that it attempts to persuade to join them in their deplatforming of Huawei.

As a crucial aspect of being a critical cartography, this research not only examines the current state that various stakeholders currently exist in, such as a nation’s current stance on possible cooperation with Huawei, but also examines the various decisions and power relations between these stakeholders that have led to their current way of being. As described by Crampton, a critique “is not a project of finding fault, but an examination of the assumptions of a field of knowledge.” (Crampton 13) He further cites Michel Foucault who formulates this as: “A critique does not consist in saying things aren’t [sic] good the way they are. It consists in seeing on what [sic] type of assumptions, or familiar notions, of established, unexamined ways of thinking the accepted practices are based.” (Crampton 13; Foucault) As an example of this, this research shows that preexisting political and economic relations are of crucial importance in deciding the stance of a stakeholder.

In order to be able to frame the controversy surrounding Huawei as a deplatforming effort specifically, this research bases itself further upon the notion by Plantin et al. that the line between infrastructure studies and platform studies has blurred in the face of rising technological innovations such as the internet, and that leaning into this notion provides a useful framework for the study of networks and stakeholders that show aspects of both platforms and infrastructures. (Plantin) One of the main decisions made by stakeholders within the context of Huawei is their decision to incorporate them or not within countries’ newly to be built 5G networks. This 5G network shows aspects of both infrastructures and platforms. As an infrastructure it is a heterogeneous network that is connected via sociotechnical gateway; it provides an essential service with public value on a large scale; and it is in large part funded by national governments. As a platform however the 5G networks at least currently are privately owned; they are competitive with other companies seeking the opportunity to work with governments in order to establish this network; and the service it provides can be viewed as non-essential due to the existence of older 3G and 4G networks. (Plantin, 299) In this light, this research frames efforts by the U.S. to make other countries opt for Huawei’s competitors for the foundation of their national 5G networks as an effort to deplatform Huawei from the platform of the international telecommunications service market. To summarize, this research looks critically at the decisions being made on a global scale regarding the incorporation of Huawei into newly to be founded 5G networks, and maps these decisions geographically for the purpose of further analysis.

II. Methodology

In order to effectively answer the research question(s), a methodology consisting of data extraction tool Lippmanian Device, a geographical mapping website mapchart(dot)net, and a designing software named Canva were utilized. The overarching motive of this exercise was to know how the U.S.’ decision to ban vis-à-vis deplatform Huawei’s 5G technology for their alleged involvement in espionage influenced other countries to act on the matter. In order to achieve the aforementioned, the major actors involved in the discourse surrounding the deplatforming of Huawei’s 5G technology was to be known.

To start with the research, the keywords [huawei], [5g], and [banned] were queried on a research browser using the search engine Google, the intent behind querying these specific keywords was to get a broader idea about the topic and also the news websites that have covered the topic of Huawei’s banning/deplatforming. Once the query results were returned, the earliest appearing ten unique news websites were selected for our further mode of data collection through the Lippmannian device.

Lippmannian Device is a data extraction tool built by the internet-research group Digital Methods Initiative (DMI). The tool queries for keywords among inputted websites across different search engines. It is also designed to do the aforementioned tasks in specific queried time frames. Using the tool, the previously used keywords [huawei], [5g], and [banned] were queried in the curated list of different news websites to know how the discourse around banning Huawei’s 5G technology has been and who are the major actors.

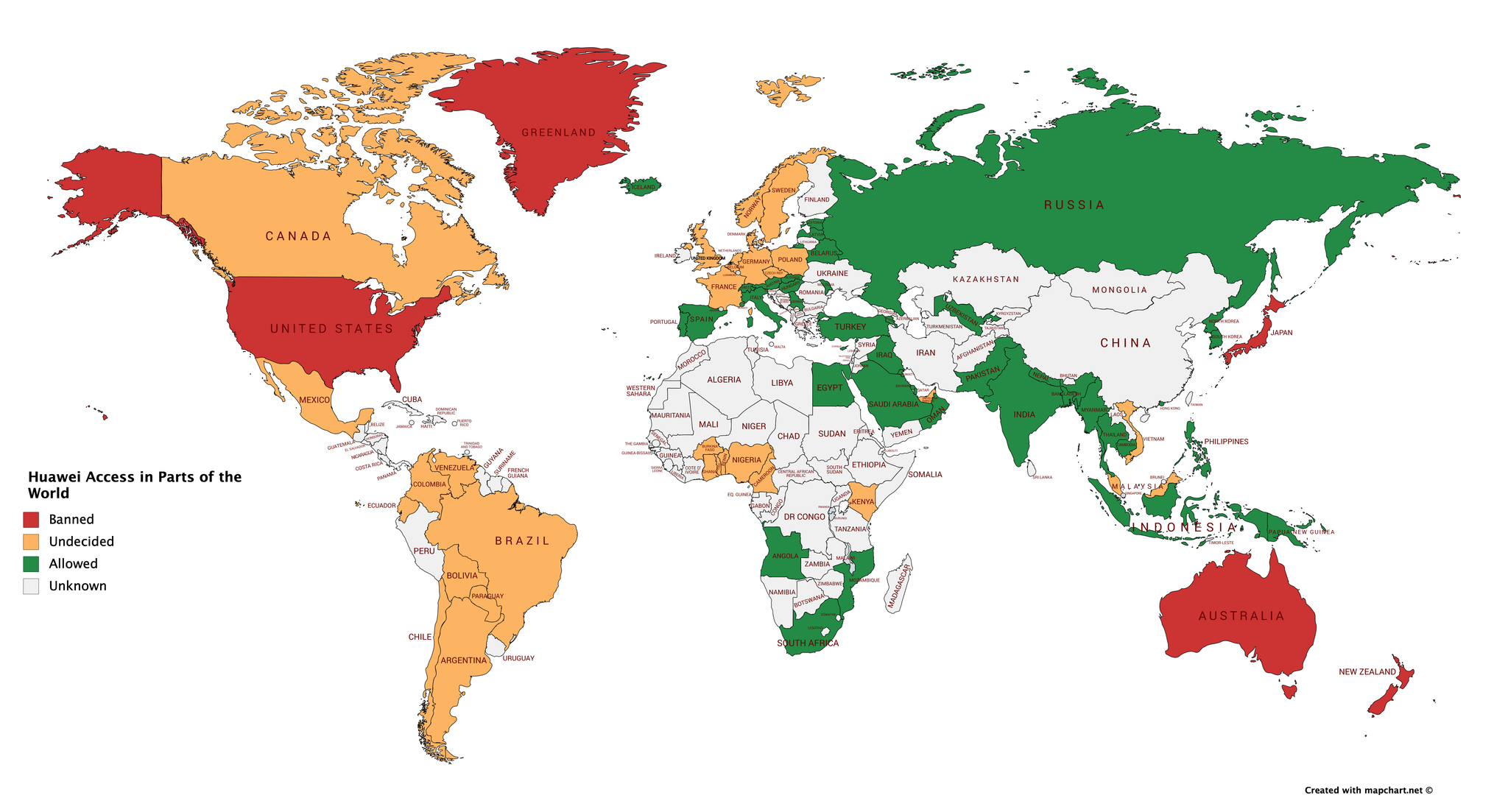

The results of this query on the Lippmanian device were retrieved in a CSV file; the file presented a list of all the news articles appearing in those ten news websites that mention the three queried keywords. Title of the article, article description, and the article url were among other information returned. Proceeding to the next step, a close reading of all the article title column and article description column was done to pull out names of different countries (potential actors in the deplatforming of Huawei). A keyword search was also done on the CSV file with country names and a list of countries. Furthermore, the articles these country names appeared in were read to know what is being written about the country in the context of Huawei’s 5G technology. It was known that not all countries are on the same page and hence all the countries were categorised into three groups, namely 1. Banned (those countries like the U.S., which imposed a total ban on Huawei’s 5G technology), 2. Undecided (those countries which were investigating the matter and the decision was awaited), and 3. Allowed (those countries which partnered with Huawei for their working). In the due course of categorising these countries, it was known that a few platforms like Facebook too had taken individual decisions on whether or not they will be partnering with Huawei; those platforms were noted down too.

Once we had a list of all the countries and their status on Huawei’s 5G technology, the website mapchart(dot)net was used to geographically colour code these countries based on their status. The website allows for users to choose a country/continent/word, add title to the chart’s legend, and choose a label/description for each colour. The countries which had banned Huawei were marked in red, the undecided countries in orange, and the countries that allowed were in Green. Other countries with no information were in grey.

Furthermore, to annotate the maps, the iterative snowballing method was used and a close reading was done on the articles that talked about these countries and a gist about every country (either a sentence or two) was noted down. The designing software Canva was then used to place the map and annotate it. After we had the map(s), they were further referred for interpretations mentioned in the ‘discussions’ section.

- III. Results & discussion

Figure 1:Map of the world indicating their stance on Huawei 5G technology

North & South America

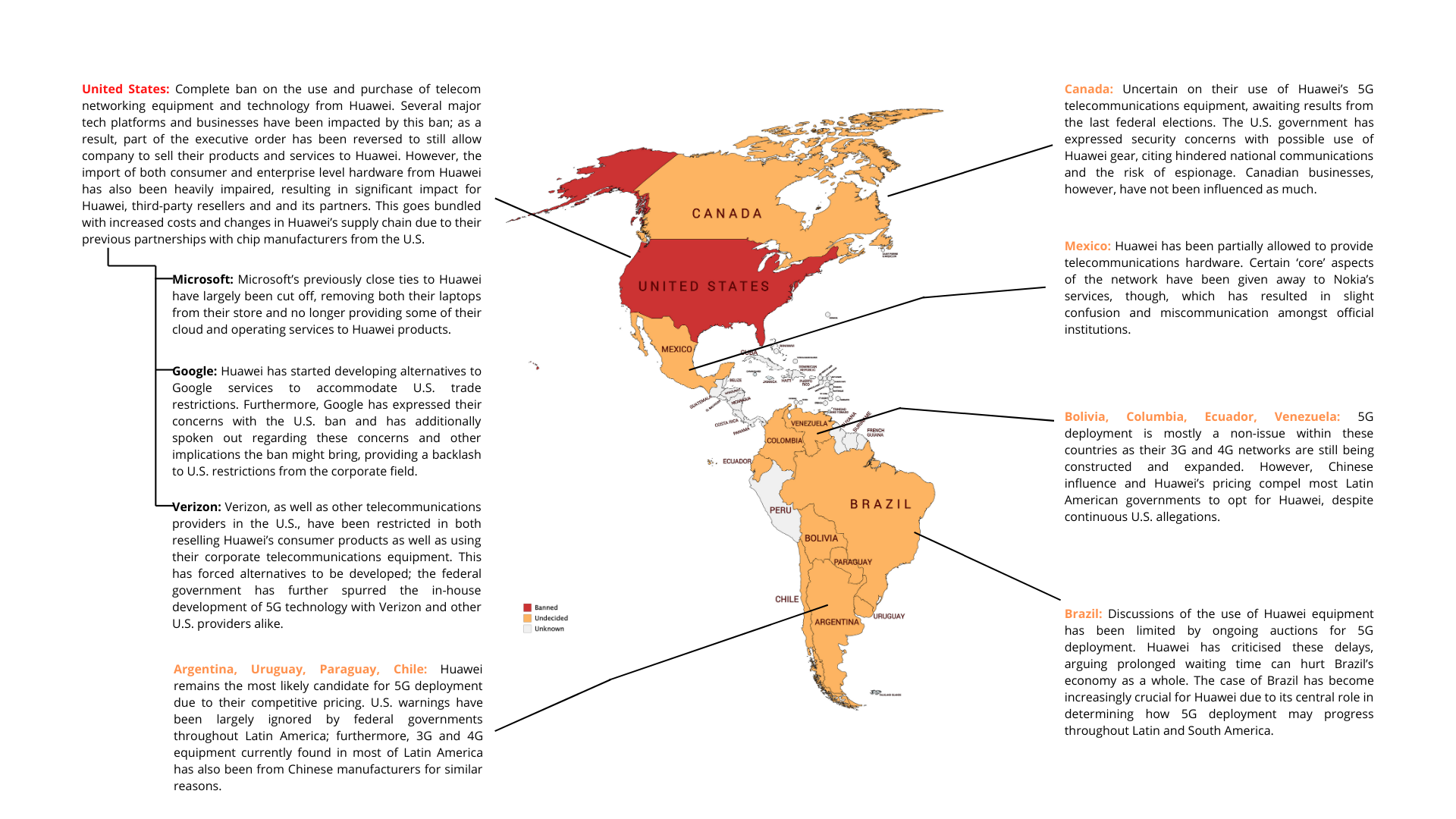

Figure 2:Annotated map of North & South America indicating their stance on Huawei 5G technology

When looking at North America and its stance on Huawei’s business and 5G deployment, most narratives are heavily centered and based around the on-going trade war with the U.S. However, when looking at the four countries involved here, one can deduce interesting deviations from the expected consensus regarding the use of Huawei technology and infrastructure. More importantly, as the U.S. houses some of the largest global tech companies, the direct implications the U.S. sanctions and executive orders have had on these businesses are also of interest here.

As seen in figure 2, no North American country has allowed Huawei to already establish some of the required 5G infrastructure, while some have outright banned the use of Huawei services. Greenland, unlike its other North American counterparts, has been influenced by the decisions of Danish telecom providers to opt for Ericsson for their 5G deployment, directly eliminating Huawei as competition. Canada has remained largely undecided in the matter; U.S. ministries have expressed their concerns with the consideration of Huawei directly and repeatedly due to the potential security and espionage risks involved (Fife and Chase). Mexico, on the other hand, provides some insight to the general consensus of Huawei that can be seen in Latin and South America; U.S. influences have been largely neglected, giving Huawei partial access to build out the Mexican 5G network in a joint effort with Nokia; this has, however, resulted in miscommunication from Mexican telecom providers due to the split efforts that were promised to either Nokia or Huawei (Love).

The U.S. has been a special case in the affairs surrounding Huawei, as they have been primarily responsible for the move away from Chinese manufacturers for telecommunications equipment. Throughout 2018 and 2019, sanctions have been placed upon trade with several Chinese businesses, including Huawei, as a result of ongoing security and espionage investigations. While these sanctions were originally intended to entirely prohibit trade with Huawei, sanctions were temporarily softened to allow U.S. companies to provide limited services to Huawei; however, this has resulted in little change, as many of the restrictions still cut off Huawei’s supply chain of high-end chips and electronics, forcing Huawei to invest in in-house development of alternatives (King). U.S. telecom providers have since been considering competitors from Europe, such as Ericsson and Nokia, as well as in-house development of new ways to deploy 5G infrastructure, despite repeated delays in a full ban of Huawei equipment and services (Porter).

Extensive sanctions and bans on business with Huawei have heavily influenced Silicon Valley’s industry giants and telecommunications in the U.S., especially in rural areas that were previously dependent on Huawei for their 5G equipment. This can be seen in both the reselling of Huawei products, as well as providing services to Huawei products and allowing the use of Huawei or ZTE technology by telecom providers. Backlash has existed to a certain extent from both Huawei and U.S. companies such as Google, with an unfair process and insufficient evidence of espionage, as well as possible compromised cybersecurity and privacy concerns cited as reasons by each actor respectively. Additionally, the sanctions placed upon U.S. companies may extend past national borders due to the inherently global influence and presence companies such as Google, Microsoft and Facebook possess, all of which have been impacted by the trade restrictions.

Despite its proximity, most South American countries seem largely unaffected by U.S. influence in their decision to operate with Huawei or its competitors for 5G deployment. The leading and deciding factor for most South American countries comes from Brazil, as other countries have closely followed steps taken by Brazilian officials in handling the situation. While Brazil has not yet decided if Huawei will aid in 5G deployment in the country, it is a likely outcome that will sway neighboring countries in the same direction; talks have been stagnant in anticipation of upcoming auctions for 5G infrastructure construction that have been delayed (Stuenkel). Countries such as Argentina, Uruguay and Chile are likely to follow suit with Brazil’s choice, deciding a significant market for Huawei as a result, as all of these countries have expressed interest in establishing 5G infrastructure.

Asia

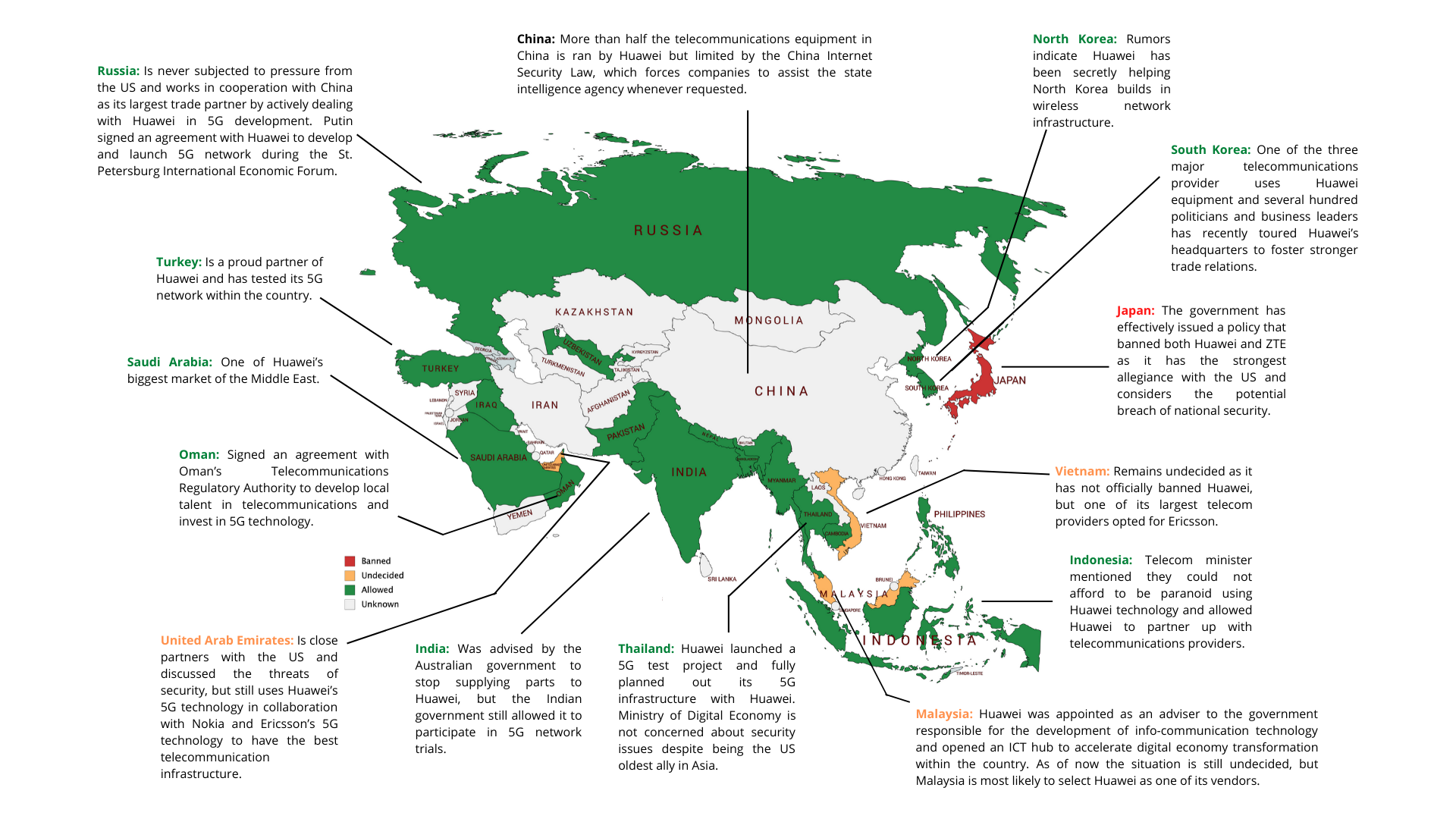

Figure 3:Annotated map of Asia indicating their stance on Huawei 5G technology

As indicated in figure 3, the trade tensions between the U.S. and China barely affected Asia in terms of deploying next generation 5G networks. The majority of Southeast Asian countries have settled their decisions and are most likely to select Chinese telecommunications equipment despite political relations with the U.S. and China.

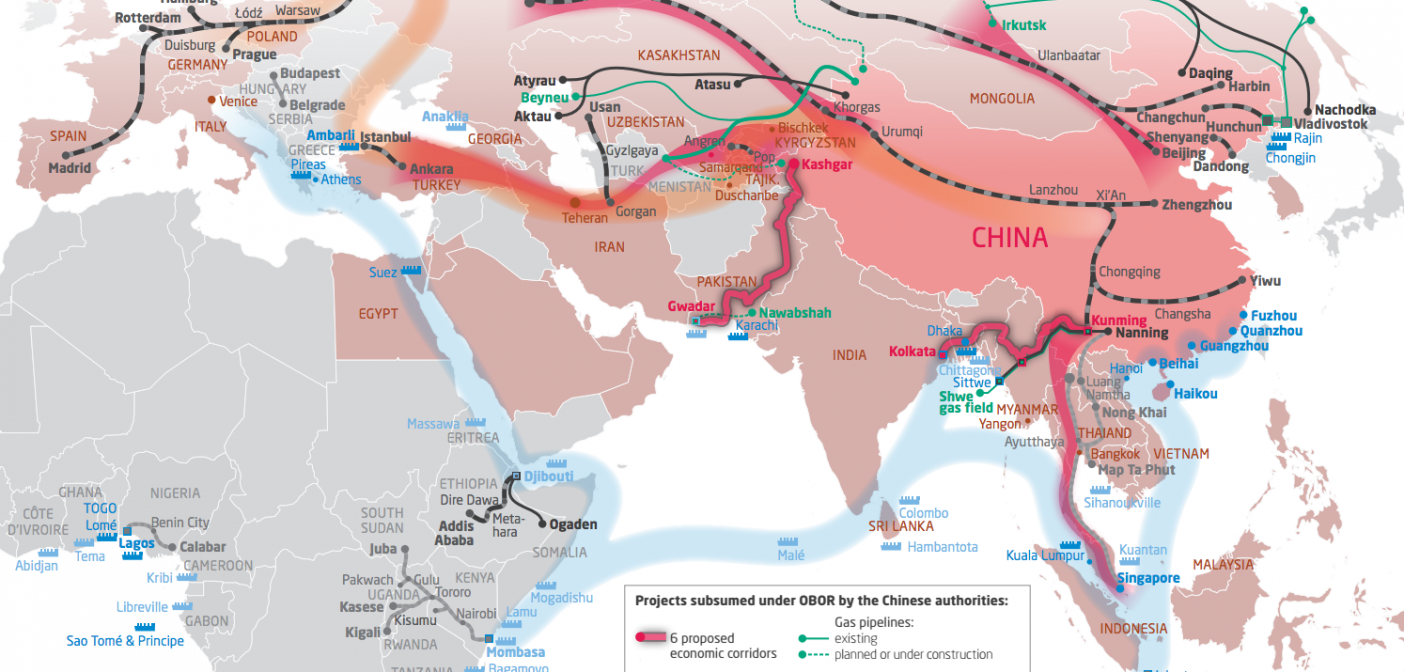

Figure 4:The New Silk Road map. Source:Mercator Institute for China Studies

Huawei has cultivated strong business relationships with most countries in Southeast Asia as it offers the cheapest and most cutting edge technology compared to other providers (Rahil). Huawei was also a key vendor for the current 4G network infrastructure in Southeast Asia as countries want to keep the same vendor for their 5G infrastructure (Vaswani). Most countries in Southeast Asia are bordering China and therefore want to keep positive trade and business relationships with China as shown by China’s New Silk Road economic corridors which spans across most Southeast Asian countries (Figure 4). The concerns about the situation made Asian governments think twice before making direct decisions. Countries like Singapore remain neutral on the situation and decide not to choose sides, while closely considering their relationships with both the U.S. and China.

In Asia, Japan is the only outlier that decided to pass on a policy that effectively excluded Chinese telecommunication equipment from Huawei and ZTE. Japan’s allegiance to the U.S. is tight and pays direct attention to the potential breach of national security when deploying Chinese telecommunication equipment. Neighboring countries like South Korea, however, recently launched commercial 5G services and one of the three carriers uses Huawei’s 5G equipment suggesting its flexibility to the situation. South Korea has strong trade relations with both China and the U.S. but has chosen a path that favors its relations with China. There were also rumors that Huawei has secretly helped North Korea build its wireless network that may violate the U.S.'s export controls to North Korea (Reuters, “Huawei Secretly Helped North Korea Build, Maintain Wireless Network”). Other major players in the region like India have also been influenced and pressured by the Australian government to stop supply parts to Huawei, but still decided to allow it to participate in 5G network trials (Reuters, “China’s Huawei Gets India Nod to Participate in 5G Trials”).

In terms of the Middle East, countries are mostly neutral about the security concerns and despite discussing U.S. restriction most countries are most likely opting to use Huawei’s 5G technology to build their telecommunications infrastructure. Huawei’s infrastructure was also present in the Middle for more than 20 years as China’s New Silk Road also crosses through most Middle Eastern countries to ensure regional business growth (Sharma). Huawei also repeatedly denies the U.S. allegations as they were visited by the Federal Communications Commission Chair (Cornwell).

Huawei’s relationship with Russia is stronger than ever as Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping signed an agreement at the 2019 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) to strengthen emerging technology (Doffman). Mobile providers in Russia have the choice to choose between Ericsson and Huawei for its 5G network infrastructure. Additionally, part of the agreement was also to integrate the Russian Operating System Aurora on Huawei phones (Russo). Overall, Russia as a powerful nation welcomes Chinese technology to build its next generation of mobile networks to strengthen its infrastructure. The relationship between both countries also tightens considering China’s New Silk Road economic belt which runs through Moscow (Figure 4).

The situation in China itself for selecting 5G telecommunication equipment is relatively strict as private corporations like Huawei must comply with the Chinese government as it unifies the interests of Chinese companies (Glosserman). Companies like Huawei are tied to Chinese law and are required to provide the government with data whenever it is requested. Huawei remains the largest telecom juggernaut in China as it was funded by the Chinese Development Bank (CDB) and Export-Import Bank which also allowed Huawei to compete on a global scale (Tugendhat).

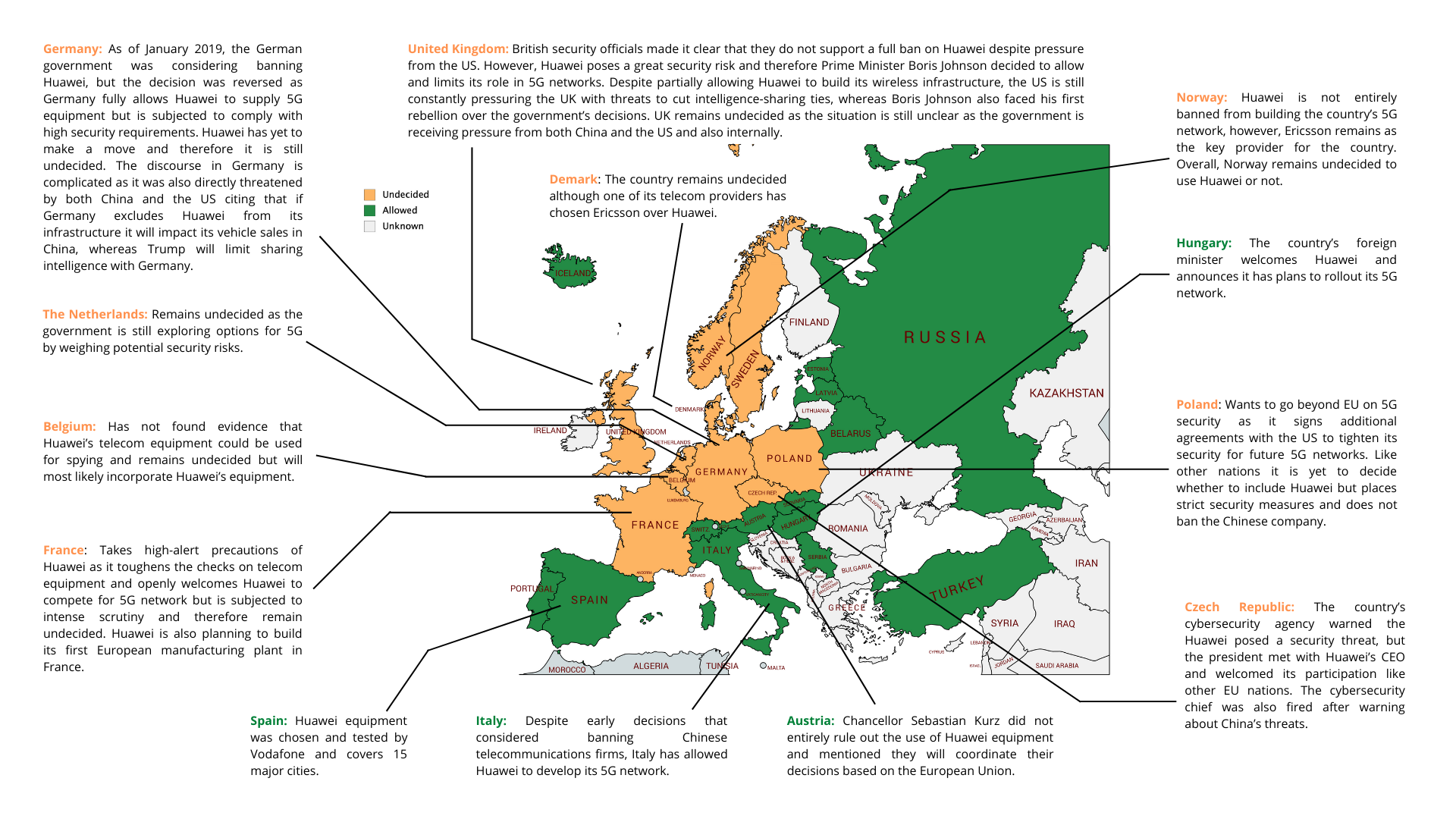

Europe

Figure 5:Annotated map of Europe indicating their stance on Huawei 5G technology

Europe as an entire continent continuously debates about the potential security risks from Chinese telecommunications equipment and has no cooperative plan to address the issues. Countries in the EU have diverse opinions on the issue and are under intense scrutiny to make the appropriate decisions. This can relate to figure 5, indicating that most countries in Europe are making dissimilar decisions, but no country has directly banned Huawei. The discourse involving the EU has also constantly changed throughout the years as it first considers proposals to ban Huawei equipment (Emmott et al.). Due to Europe’s large market, Huawei was also petitioning to face extra security measures, while the European Commission urges EU countries to share data to tackle the cybersecurity risks as they ignore the pressure from the U.S. to completely ban Huawei (Chee and Emmott). Ultimately, most EU countries ended up tightening its process to select 5G suppliers and made it harder for Huawei to dominate the market as EU countries opted for Sweden’s Ericsson, Finland’s Nokia, and South Korea’s Samsung. Countries like France and Germany are trying to remain neutral as they are pressured by both the U.S. and China and therefore need to make appropriate decisions to satisfy both countries. Major EU countries are also in close relationship with China according to the New Silk Road economic belt that solidifies trade relations between China and countries like the Netherlands, Germany, and Spain (Figure 4).

With the UK breaking apart from the EU, the situation remains unclear within the UK as it faces similar challenges to Germany. The situation in the UK is more intense compared to countries within Europe as British officials do not support a full ban of Huawei (Stubbs and Singh). The government continues to monitor the situation precisely as it has considered a potential ban in March of 2019 (Martin). The security risk Huawei poses made it challenging for the UK to reconsider its decisions until the U.S. comes clear with the Chinese company. After Britain's new prime minister Boris Johnson has been elected, he continues to postpone decisions while constantly being warned and threatened by U.S. National Security Adviser that it may cut intelligence-sharing ties (Stubbs and Alper). Telecommunication network providers in the UK are urging Boris Johnson to not ban Huawei as it may slow down the rollout of the 5G network as he finally allowed Huawei a limited role to Britain 5G network in January of 2020 (Sandle and Stubbs). This ultimately angered the U.S. and asked the UK to look back at its decision and cautioned that American information should only pass through trusted networks (Faulconbridge and MacLellan). Like EU countries the UK is also tightening the security of the country’s 5G network by limiting Huawei’s market share. The situation in the UK has gotten worse when Boris Johnson faced his first rebellion over his decision to allow Huawei, but he was able to defeat the decision in March of 2020 (Sandle and MacLellan). Overall, the situation in the UK is still tempestuous as it constantly gets pressured internally by clashing organizations and parties while getting threatened by the Trump administration. UK’s trade relations with China are also on the line as it is trying its best to give Huawei a limited spot to help develop the region’s 5G infrastructure.

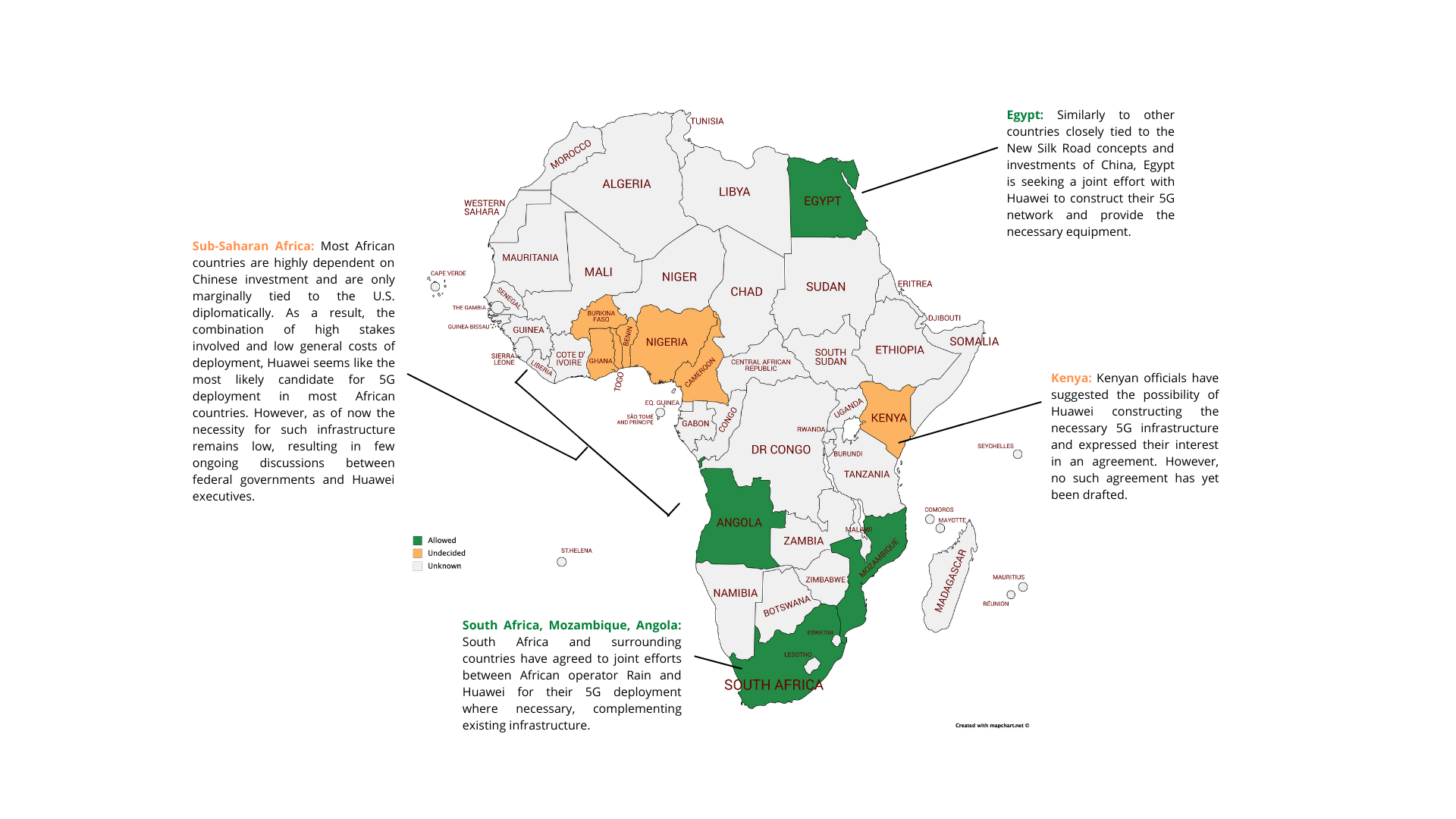

South America & Africa

Figure 6:Annotated map of Africa indicating their stance on Huawei 5G technology

Additionally, one further notion to consider is the already consistent presence of Huawei’s equipment in South America. Most South American countries currently operate their 3G and 4G networks with Huawei-built infrastructure due to its pricing, a far more important factor to consider as opposed to international security concerns fronted by the U.S. This inherent bias towards the company may be a tipping point for many South American countries looking to establish a 5G network. These trends can also be observed in African countries, especially those heavily dependent on Chinese investment as a part of the previously mentioned New Silk Road projects, such as Egypt and sub-Saharan countries such as Kenya. South Africa, Mozambique and Angola have already allowed Huawei to construct 5G infrastructure in a joint venture with African provider Rain (Baldock), thus leading the initiative of 5G deployment in Africa.

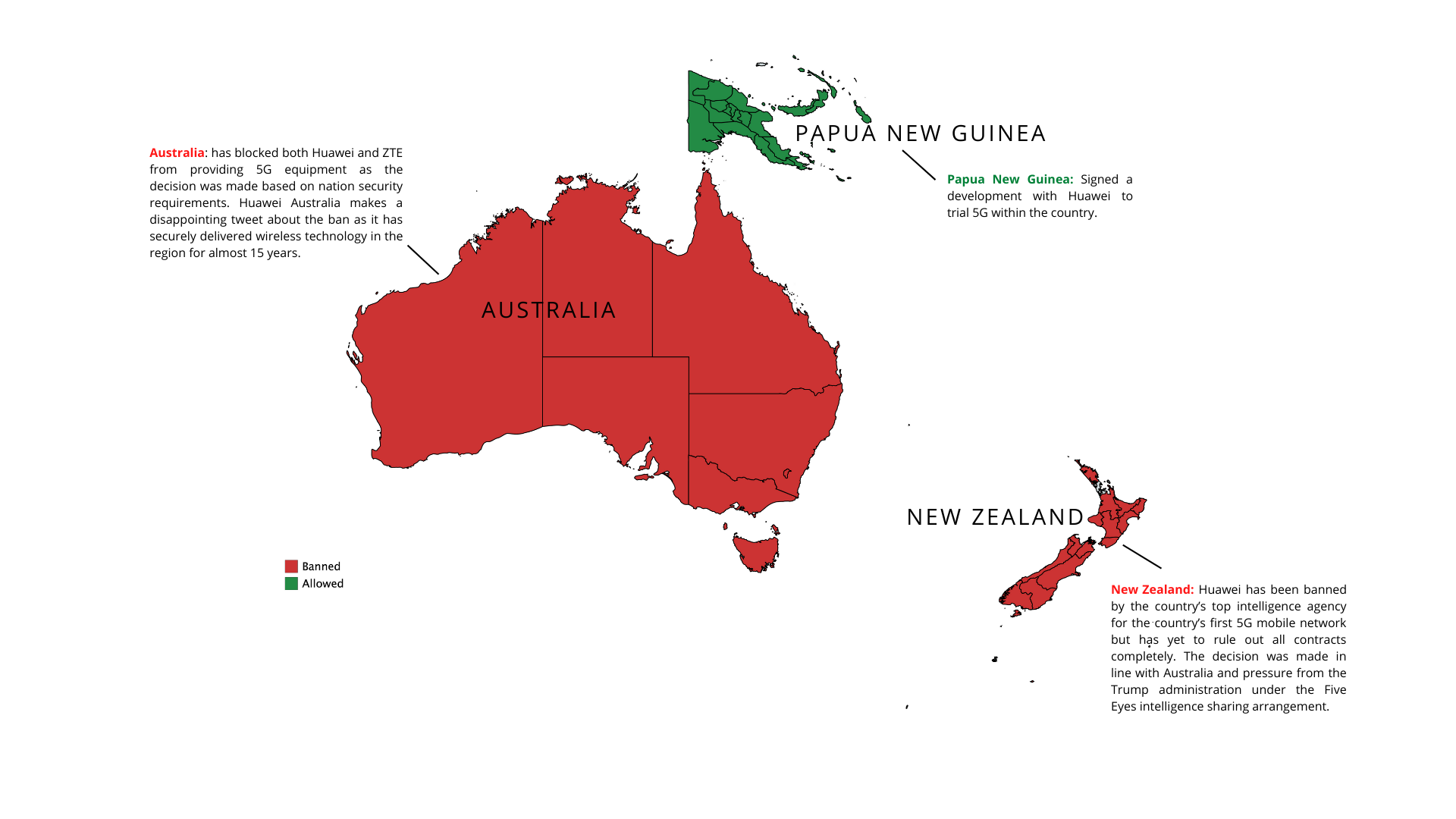

Oceania

Figure 7:Annotated map of Oceania indicating their stance on Huawei 5G technology

The two main countries of this continent are Australia and New Zealand who are members of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing arrangement with the UK, Canda, and the U.S. who constantly pressures them to block Huawei due to its national security concerns (McDuling). Oceanic countries are generally concerned about the new Chinese law that obligates Chinese organizations to provide information to government agencies whenever needed (Shu). It especially states that 5G technology introduces new risks if compared to previous generation technology as Australian operations are not bound to Chinese laws and have the right to refuse to hand over information to the Chinese government. The announcement made by Oceanic countries also came promptly after the U.S. has decided to blacklist Chinese companies, suggesting that they act in accordance with the U.S. suggestions and fear the national privacy breaches. Despite the concerns, other minor nations within Oceania have allowed Huawei to conduct trials within their country due to its cheap and efficient offerings.

Conclusion

This research set out to explore the different narratives surrounding Huawei and the use of Chinese-made 5G infrastructure, as well as the role U.S. diplomacy has played in the matter. As this is an ongoing debate, the resulting maps can be seen as contemporary reflections of international trade that resulted from Huawei being deplatformed from the U.S. market. As demonstrated in the discussion, there is a clear and distinctive notion of security that is present in all discourse regarding Huawei. Secondary topics such as privacy and espionage are also touched upon. However, by mapping out the current status of Huawei and 5G deployment in different countries across the globe displays that the Chinese international relations, investments and ongoing and existing projects play a major role in either allowing or banning Huawei services. A direct correlation can be drawn to the New Silk Road, which aims to connect modern day China and its flourishing economy to Western countries as well as developing nations; those directly influenced by these projects are heavily skewed in Huawei’s favour. This also leads to the intrinsic preference of countries already working with Huawei to continue to support their services; a notable exception are Japan, who is heavily tied to the U.S. in terms of diplomacy and economic welfare.

The impact of ongoing affairs can be seen globally, but are nonetheless mostly originating in the U.S. due to its large share of internationally operating corporations that are directly hindered by U.S. sanctions. This, combined with a strong diplomatic bond between the U.S. and Europe, has also contributed to hesitation in European countries to adopt or ban Huawei, instead focusing on preserving security wherever possible. As such, the deplatforming efforts of U.S. official institutions have been noticeable, but not all-encompassing on a global scale, thus only limiting both the reach and options at Huawei’s disposal to a certain extent.

There is one major limitation to this research as the discourse around the usage of Huawei equipment can periodically change depending on the decisions of superiors, which could directly impact the relational analysis of this research. The mobile networking landscape is currently transitioning from 4G to 5G technology; therefore, superiors are constantly pressured to make appropriate decisions to efficiently upgrade the country’s infrastructure. In the case of platforms, any minor or major update of policies and laws can easily impact the outcome of their services and are also forced to appropriately adapt to the situation. The discourse may also change depending on the results of the upcoming 2020 U.S. presidential elections as it was Trump’s administration that blacklisted Huawei and pressured other nations to cooperate. Thus, it is more appropriate to conduct this research when 5G technology has successfully been installed and implemented to map stable relations and make concrete connections between actors.

0 Comments Add a Comment?