Twitter as a storytelling machine: Framing the Sudanese Revolution through Tweets

Twitter & Arab Spring 2.0

The Middle East has been witnessing tremendous growth of digital media like Twitter, which has played an important role in public, real-time conversation and information exchange (Bruns and Weller, 2016). Researchers have observed an increasing integration of digital technologies in social movements into their organizing and claim making processes. Traditional media often marginalizes protest actions by distracting people from the underlying reasons to dramatic actions, so political activists have turned to an alternative public sphere to reach the public and their policy makers. The unique features and affordances of Twitter make it possible for protestors to voice out different perspectives, establish a sense of community and express solidarity (Harlow and Johnson, 2011). In the digital media era, Twitter goes beyond its function of sociality, and becomes a significant alternative tool for online political activism, or cyber-activism, which is defined by Philip Howard (2011: 145) as “the act of using the internet to advance a political cause that is difficult to advance offline”.

Twitter’s power as a social media platform has been utilized in several political movements during the Arab Spring, which led to the downfall of long-standing regimes in the Middle East and North Africa. The increasing use of Twitter in political movements is often referred to as the “Twitter Revolution” by scholars. Recent academic research investigates the importance of social media in social movements, how political protests portrayed on social media affect people’s perception towards them, and how it facilitates inter & intra-group communication and information dissemination (Tufekci & Wilson, 2012). Only a few studies believe that social media brings negative effects to political movements (Adey et al., 2010), while others regard it as useful communication platform (Howard & Parks, 2012). In addition, research also examines whether the news coverage on social media falls into the “protest paradigm” that might impact the credibility of the protest (Harlow and Johnson, 2011). Previous research has investigated the role of social media from different aspects, but few of them conduct integrated research from both the perspective of global news coverage against that of Tweets.

This paper aims to explore the role of Twitter in social movements from both sides. To conduct the research, we chose the Sudanese Revolution as a case study, as it exemplifies a typical political movement that was closely engaged with Twitter. The Sudanese Revolution is a recent event that took place from December 2018 to September 2019, during which the long-standing dictatorship president Omar Al-Bashir was toppled by people’s strong demands of democracy in Sudan. In June, the movement experienced a violent crackdown by authorities, also referred to as the “Khartoum massacre”. Over a hundred people were killed during the crackdown by military forces. As the news about Sudan revolution and the crackdown are blocked or rather very limited in mainstream media during the revolution, people turned to Twitter for public support and to spread awareness. They used hashtags such as #BlueForSudan, #sudanrevolts and #IAmTheSudaneseRevolution to express advocacy of the revolution and remember the people who have died in this movement (Picture 1). The 2019 Sudanese Revolution is also often considered as the Arab Spring 2.0, as the political activities are similar to those carried out in the Arab Spring, but it has even more Twitter engagement and exposure in the organization and promotion of events.

(Figure 1 Online campaign of Sudanese Revolution. Source: The Guardian)

As the local news coverage was significantly limited during the revolution, Twitter became a key player in understanding the whole story of the revolution. Therefore, we chose the Sudanese revolution as a case study to examine whether or not the news coverage falls into “protest paradigm” or not and how Twitter users discussed this event online, in order to figure out an integrated storytelling by collecting data on Twitter. The following research questions will be investigated: How did the global news media report the Sudanese revolution? Subsequently, how did the global twitter discuss the events reported?

Research Design & the role of DMI-TCAT

In order to effectively attend to both aspects of our research question, a methodology involving the research tool DMI-TCAT was designed. DMI-TCAT is a Twitter capture and analysis tool developed by the internet studies research group Digital Methods Initiative. Our study mainly intends to assess how the global news media and global twitter reported and discussed the downfall of Sudan’s (then) ruler Omar Bashir. The reason for this comes from a vantage point that the internet was banned in Sudan during the course of the revolution and the local news media was not active. Hence, the only place where we could effectively gauge the pulse of public reaction to this critical political development was twitter. Given Twitter’s “What’s happening” era and globally widespread usage, it makes a better fit to assess socio-political discourse compared to any other social media platforms like Instagram or Facebook.

The immediate week after Bashir’s downfall i.e., 11thApril, 2019 to 17thApril, 2019 was chosen for our study. The Sudan Twitter-dataset managed by DMI consisted of tweets made using the hashtags and keywords ‘#sudanrevolts’, 'Sudanese Revolution', ‘Al-Bashir’, ‘Sudan’, ‘sudanrevolts’, ‘SudanUprising’ and ‘Sudan_Revolts’. This dataset was effectively made use of in our research as it contained tweets from our required timeframe. The total number of tweets in the dataset were 245,461,861 and the tweets in our duration of research were 660,721 made by 295,174 distinct users.

The first step of the study was to conduct research on how global media reported the event. Here, we intended to look at the top English news media portal’s tweets that mentioned the keyword ‘Sudan’ and contained a weblink (URL). The idea behind this was an assumption that the tweets made by news organizations in the queried duration of time with the keyword ‘Sudan’ and a web-link would definitely be a news article written by them on the ongoing developments. A list of the top 5 global English news media organizations based on their Twitter follow count was made. The news organizations were CNN (56.1 million followers), New York Times (44.6 million followers), BBC (26.3 million followers), Washington Post (14.5 million followers) and Al Jazeera English (5.64 million followers). In the next step, a ‘user-specific’ query was made; here we entered a news media organization’s twitter username in the ‘From User:’ box of DMI-TCT and the ‘(Part of) URL’ box was filled with the specific news organization’s website link. The start-date of the query was filled as 11th April, 2019 and the end-date as 17th April, 2019. This particular query returned us with the tweets that the news organization had made containing the keyword ‘Sudan’ in the selected timeframe along with an article/link from their website. This exercise was conducted with all the 5 news organizations selected and the results (tweets with links) returned were saved and visualized (a total of 110 articles). However, this doesn’t fully answer the first part of our research question which intends to know “how” global media reported the issue. Hence, we did another round of queries, where we posted the news article links in the ‘(Part of) URL’ box of DMI-TCAT, filled the same start and end date and ran a query which gave us the number of tweets made by public using that specific link. By doing the same for all the news articles, we shortlisted top 10 most engaged news articles related to ‘Sudan’ by the public. Further, a qualitative analysis of the news articles was done to know the popular frames/angles of news that the public shared or tweeted the most, which can be known as the Framing Analysis. By learning the most popular news frames/angles on Sudan’s revolution reported by global media, we effectively answered the first part of our research question.

Coming to the second part, our research question here intends to assess how the global public discussed the events in Sudan. As a first step, a query with the keyword ‘Sudan’ was made in the data set. Millions of tweets were returned. Using DMI-TCAT’s tweet statistics and activity metrics, the Hashtag frequency of the dataset was known. #SudanUprising emerged as the most popular hashtag in the dataset. Using this hashtag, a query was made for the first day of our study (April 11th, the very day of Bashir’s downfall). Around 66,000 public tweets were returned. Under the tweet-exports category of DMI-TCAT, a randomized set of 1000 tweets from the queried day were collected. It was seen that a majority of these 1000 tweets were retweets/reblogs. After a bit of sorting, 100 unique tweets from the day were selected for a qualitative analysis. This experiment was conducted across the 7 days of our research period. A total of 700 tweets were selected for a close-reading to form an opinion on the most popular frames/angles of opinions shared by the public (Framing analysis again). DMI-TCAT by default had already returned us with 1000 randomly selected tweets of the day, we further did a random-sampling of tweets without letting our opinions/bias paving way in the selection, hence the total 700 tweets collected can stand as a good representative of the opinions of global twitter in those 7 particular days. Through this, we answer our second part of the research question: ‘how’ global public discussed the events. A close reading was done to compare the frames of news/opinions reported by the news media organizations and the frames of opinions tweeted by the public. Further, a media critique was done to highlight the disparity of opinions between global news media and global twitter and shed light on how they received or understood the political developments happening in Sudan. The forthcoming sections of the study present the findings and the important points of discussion in our research.

To talk about the limitations of the study: the sample size of tweets and articles selected was not actually fully representative of the dataset. The disparity in the number of available tweets and the chosen tweets for analyses is in the millions and hence it acts as a limitation. Among the chosen tweets, it is a tricky call to claim they were representative of all frames/angles of public opinions as Twitter only represents a ‘narrow sliver’ of the public, and of this sliver is an even narrower slice of users who engage with a given issue on Twitter (Mitchell & Hitlin, 2013). The language barrier is an added limitation as many tweets related to the Sudan issue were being made in the local language, Arabic, and the tweets didn’t include hashtags and keywords in English, as a result of which, the DMI data set on Sudan could collect only those tweets that had English hashtags while the language spoken at point-zero was not English.

Findings

The Global News Media Coverage & The East-West Contrast

When looking at the findings considering the global news media coverage on the Sudanese Revolution, it becomes apparent that the most circulated news articles stem from the news source Al Jazeera. This in itself is an interesting finding, as Al Jazeera is a news source based in the Middle-East. This while more Western news sources such as the BBC or CNN were in minority when looking at the news coverage surrounding the Sudanese Revolution. Furthermore, what is standing out, is that the articles by Al Jazeera were mostly shared on Twitter, which could be given their credibility in the Arabic region.

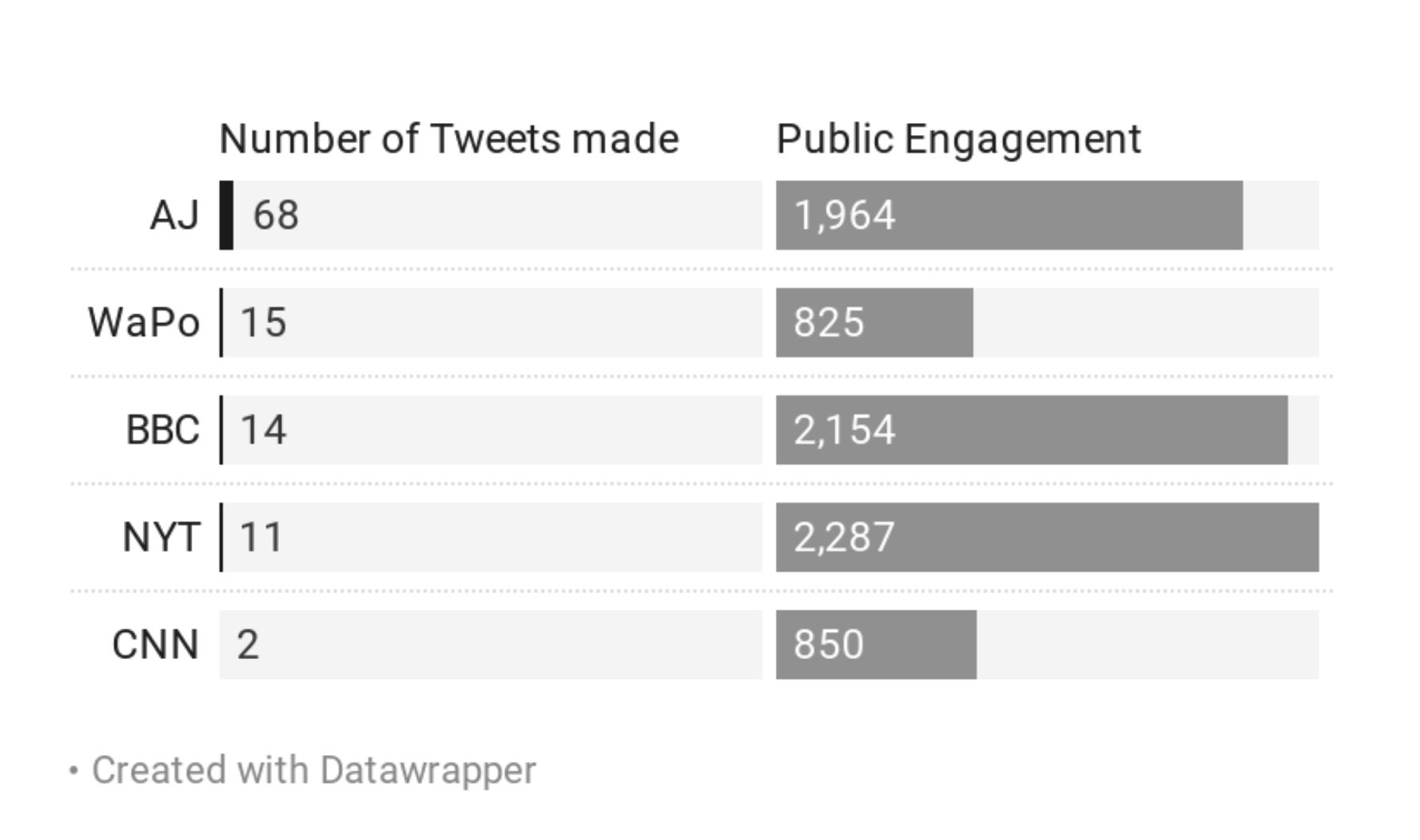

Above that, what became prominent when considering the global news media coverage on the Sudanese Revolution, is that while Al Jazeera had the highest number of Tweets made pertaining to this event, their engagement was lower than the New York Times and the BBC. Even though, the New York Times and the BBC both had a significant less amount of Tweets surrounding the Sudanese Revolution, as illustrated inFigure 2.In addition, when considering the content of the most engaged with news articles surrounding the Sudanese Revolution, it becomes apparent that most articles are feature articles that talk about the history and origins of the Sudanese Revolution. For instance, they had an emphasis on explaining what sparked the revolution, rather than focussing on reporting the actual events taking place during the protests and periods of violence.

Figure 2

Global Twitter’s Reception of the Sudanese Revolution

The tweets posted the first few days after the downfall of Omar Bashir, seem to have a positive undertone. People are expressing their happiness for the downfall in various ways. For instance one Twitter user tweeted “Their voices have been heard, their lives and well-being considered first that's a real wise transition #SudanUprising”.Besides that, there are a few Tweets with links to articles explaining what was happening right after the downfall of Omar Bashir. What’s also interesting is that some of the Tweets posted made connections to popular culture to express their thoughts. For example “Game of Thrones S8 live in #Sudan #SudanUprising #GOT #GamesOfThrones”,and “"Thank you, next" is actually written about Sudanese Presidents #SudanUprising #سقطت_تاني”.After the first two days after the downfall of Omar Bashir, we see a shift in the content of Tweets posted surrounding the Sudanese Revolution. Rather than Tweets expressing happiness or opinions about the downfall, the Tweets started to become more informative about what actually was happening in Sudan. People seemed to be confused about the events, and Tweets referring to articles explaining the situation were functioning as a way to stay updated. An example of such a Tweet is the following: “@errfnern: Everything You Need to Know About What’s Happening in Sudan Right Now: Part I #SudanUprising #اعتصام_القيادة_العامةhttps://t.co/7byCNxirmn”. The situation in Sudan seemed to have become more vicious, as reflected in some of the Tweets, such as #اعتصام_القيادة_العامة#لم_تسقط_بعد#SudanUprising #الشارع_بس #تسقط_بس 4 months of sweat, blood, tears, death, torture, sacrifice & heartache, only to be snatched by a warlord. Burhan is just a face, Hemetti runs the show. Unacceptable!”.Towards day 6 to 7 after the downfall of Omar Bashion, the content of the Tweets posted.

Discussion: Agenda Setting & Framing of Socio-Political Events

Comparing the findings from user Tweets with the findings from our sample of news articles provides interesting insight into the ways in which mass media sources frame certain events. Following Lippmann’s (1922) conceptualization of agenda-setting, traditional media can – and often do – frame events in a specific way in order to feed a particular agenda. Given that traditional media, such as news sources, are a form of one-to-many communication, these sources have the power to mould public perceptions of current affairs. The agenda-setting theory is based on the assumption that mass media outlets pick and choose to report certain events over others, based on their perceived importance. In the case of our findings from the our corpus of news articles, we note that most of the articles frame the events of the revolution through a historical lens – that is, they tend to focus on the history of Sudanese dictatorship and rebellion, as well as the reasons behind the uprising, rather than reporting the atrocities taking place at the time of the protests. The articles that did describe the violence of the military forces were written only after a consensus was reached regarding the establishment of a new democratic government. Furthermore, one particular article was dedicated to describing the incident of Pope Francis kissing a Sudanese protestor’s feet as an act of solidarity. This also reveals the tendency of news sources to report more sensational stories, as they are more likely to be circulated and shared.

On the other hand, our corpus of Tweets reveals a much more different and diverse frame of events surrounding the revolution. Ideas commonly observed across our corpus include the role and significance of women in the revolutionary protests, the demand for a democratic future for Sudan, celebratory sentiments in response Bashir’s ousting, and simultaneous sentiments of grief for the lives lost in the process. Much anger was directed at the military forces that took matters into their own hands after Bashir’s ousting and resorted to acts of extreme violence. We also noted a significant amount of links embedded in Tweets that included images and videos from inside Sudan. Interestingly enough, only a handful of these images and videos were appropriated by global news sources in their articles. Many tweets also expressed concern for the uncertainty of the future, and the persistence of protestors demanding for structural change. A common theme in these tweets was a consideration of “What’s next for Sudan?” Unlike our corpus of news articles, our sample of Tweets reveals a much more diverse framing of the revolution [in our given time frame], including specific events, a variety of emotional expressions and a more elaborate depiction of all that was taking place. This contrast can be credited to Twitter – and more, generally, social media – being platforms enabling freedom of speech for users, allowing users to say whatever they want, without any editorial interference (Rogers, 2013). This point is further reinforced by Gillespie (2017), who asserts that platforms [such as Twitter] are comprised of diverse, sometimes overlapping and contentious communities. Furthermore, these platforms maintain a certain impartiality to its ‘passengers.’ Therefore, as a platform, Twitter maintains a lack of responsibility for its users and how they are using the platform, unlike traditional media. It is therefore interesting to examine the differences in how certain events are framed when there is a lack of content regulation (Rogers, 2013).

It can be argued that given the nation-wide communication restrictions at the time, as well as the lack of coverage by local media outlets, global news sources were relatively unaware of the events taking place on ground zero. This may be the reason behind these articles’ focus on Sudanese history and Bashir’s 30-year dictatorship. This is further reinforced by the fact that only a handful of images and videos from inside Sudan went viral. Therefore, while these news sources can be criticized for failing to accurately report the events surrounding the revolution, it should be noted that like the rest of the world, the journalists writing these articles were also unaware of the specifics of the events taking place. It can also be argued that as a result of this lack of information from these otherwise trusted news sources, many people took to Twitter to both spread awareness and gain a more fruitful understanding of the occurring events. This can also be attributed to the shifting role of Twitter as an issue space as well as a site for the organization of awareness and dissemination of news-worthy information (Rogers, 2019). It is this shift, or as Rogers describes, the ‘debanalization’ of Twitter that makes it an apt platform for the research we have undertaken. This debanalization is exemplified by the shift in Twitter’s Tweet prompt from “What are you doing?” to “What’s happening?” in 2009 (Meyer, 2019). In addition, the specific platforms affordances of Twitter, such as hashtags, retweets, and quote tweets, enable the platform as an object of research and facilitate remote event analysis (Rogers, 2013), as is the case in our research. These affordances allow for a close examination of Tweets that have been engaged with the most, as well as the most common frames being used.

Conclusion

The Sudanese revolution marked a new period in Sudanese history. The events that transpired during the revolution have led to a transformation of the Sudanese political landscape. While there is still much to recover and develop in the nation, the revolution has been viewed as a success by both Sudanese people themselves, as well as the global community. One cannot dismiss the role that social media – and, in particular, Twitter – played in the outcome of the revolution. Not only did Twitter’s specific platform affordances facilitate the dissemination of immediate information and increase global awareness, but it was also used as a site for Sudanese civilians both inside and outside Sudan to express solidarity and organize activism – which global news media failed to do. While we do maintain the criticisms of labelling Twitter as a news source, our findings reveal much about the increasing debanalization and repurposing of Twitter as a platform for political activism as well as information curation.

-

PS: This article is a result of collaboration between me and 3 other peers of mine from the University of Amsterdam.

0 Comments Add a Comment?